Paper Prototyping Fateweaver

From game design classes to paper prototyping our new game. We’re moving fast over here.

Paper prototyping is the idea of making a physical version of your game so that you can play it as quickly as possible. This doesn’t mean making nice art assets or finding the perfect meeple. It’s very much the idea of a minimal viable product that gets you playing faster.

This doesn’t work for all video games of course. There isn’t much benefit for trying to paper prototype a platformer or a huge open world game. Unless you can boil down a part of those games into a form that can be simplified enough to play by hand.

By having quick access to a playable version of your game idea you can start testing out your design. Do the rules make sense? Is it too easy? Can a player complete the game? Does it need more cards or less cards? If you can paper prototype it, you can test it, toss it, iterate on it, in less time than it would take to program your original idea. It’s this time save that makes paper prototyping so useful. Instead of spending a month developing a minimal digital version you can have something going in an hour. You can even have other people playing it before even opening a game engine. As a young studio with minimal runway, this felt like the obvious path forward for our new game.

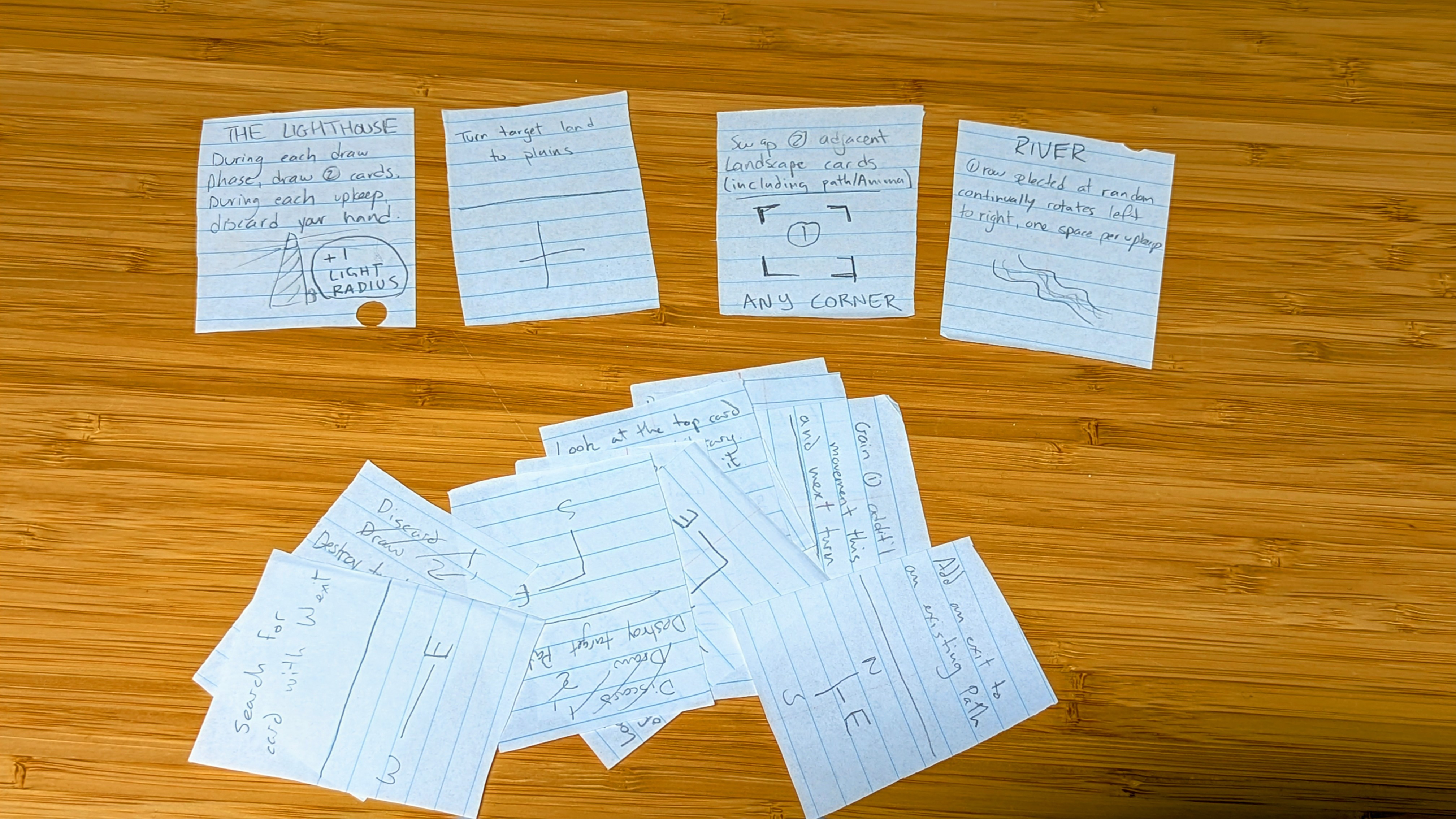

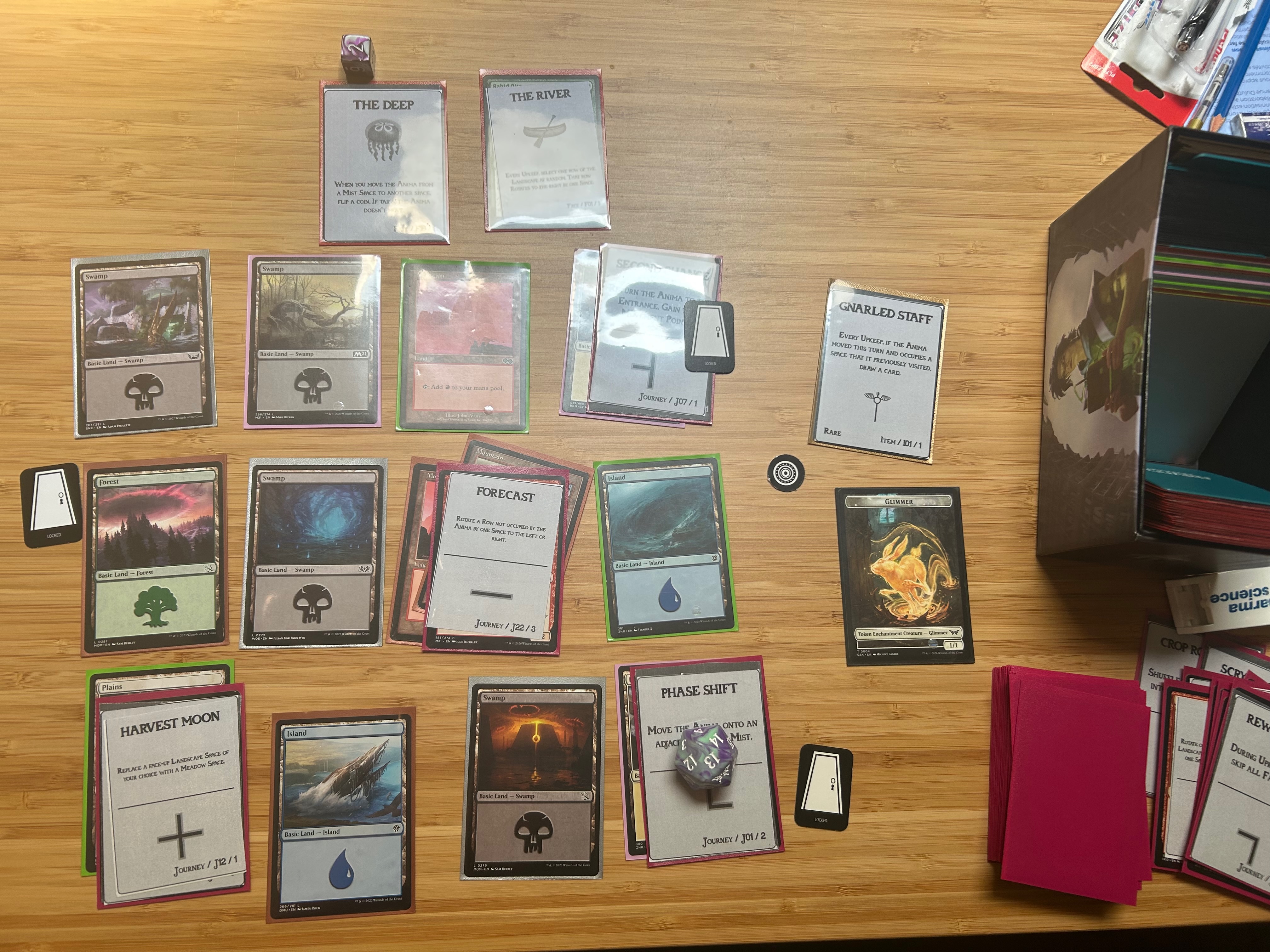

So we cut some sheets of papers into smaller rectangles, created a few cards, and started playing.

Round one

The first version of our cards were cut up lined loose leaf paper. We had our concept only in our heads, we hadn’t even tried to align on rules between each other yet. We sat down, created the most basic cards for getting the idea across and tested out what we imagined the flow to be.

Because we were moving so quickly we were making up cards on the fly, making edits by pulling the paper out of the sleeves and building out the basic concepts while also making our first round of assets.

This felt very promising after just two hours of trialing ideas. We didn’t have to buy anything to even do it, but we left the exercise feeling the potential of the game.

CIDEr (Card IDE)

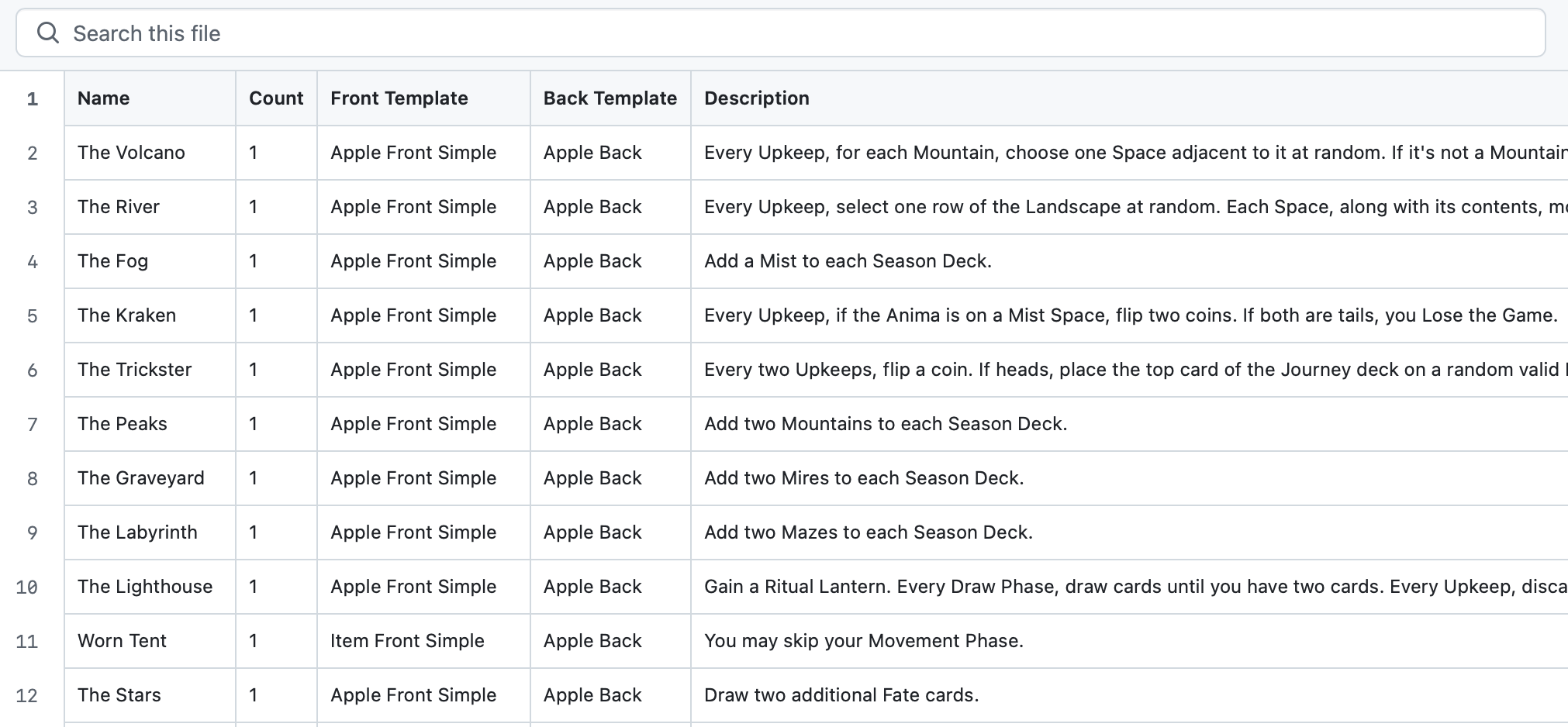

Our hand cut and hand written cards didn’t last long. After dedicating some time to card ideas we wanted a better way to manage and track our unique decks. Turns out there are multiple tools for this as people love card games.

We ended up going with CIDEr.

CIDEr lets you create both the text and visuals of the cards and provides a template for exporting them to PDF for printing. It uses HTML and CSS as a layout engine with real-time previewing, so it was quick and easy to get a basic design going for the various card types. We still needed to cut out each individual card from the printer paper but we no longer had to write out each card by hand. And now our card list and styles can live over on GitHub so it’s easier for the two of us to collaborate. GitHub also makes versioning a snap. All the cards end up in a .csv file which we hope to then feed into Godot directly to generate the cards in the engine when we’re ready. Overall, despite its low version number, it's an excellent piece of software I would recommend to anyone interested in designing a card game.

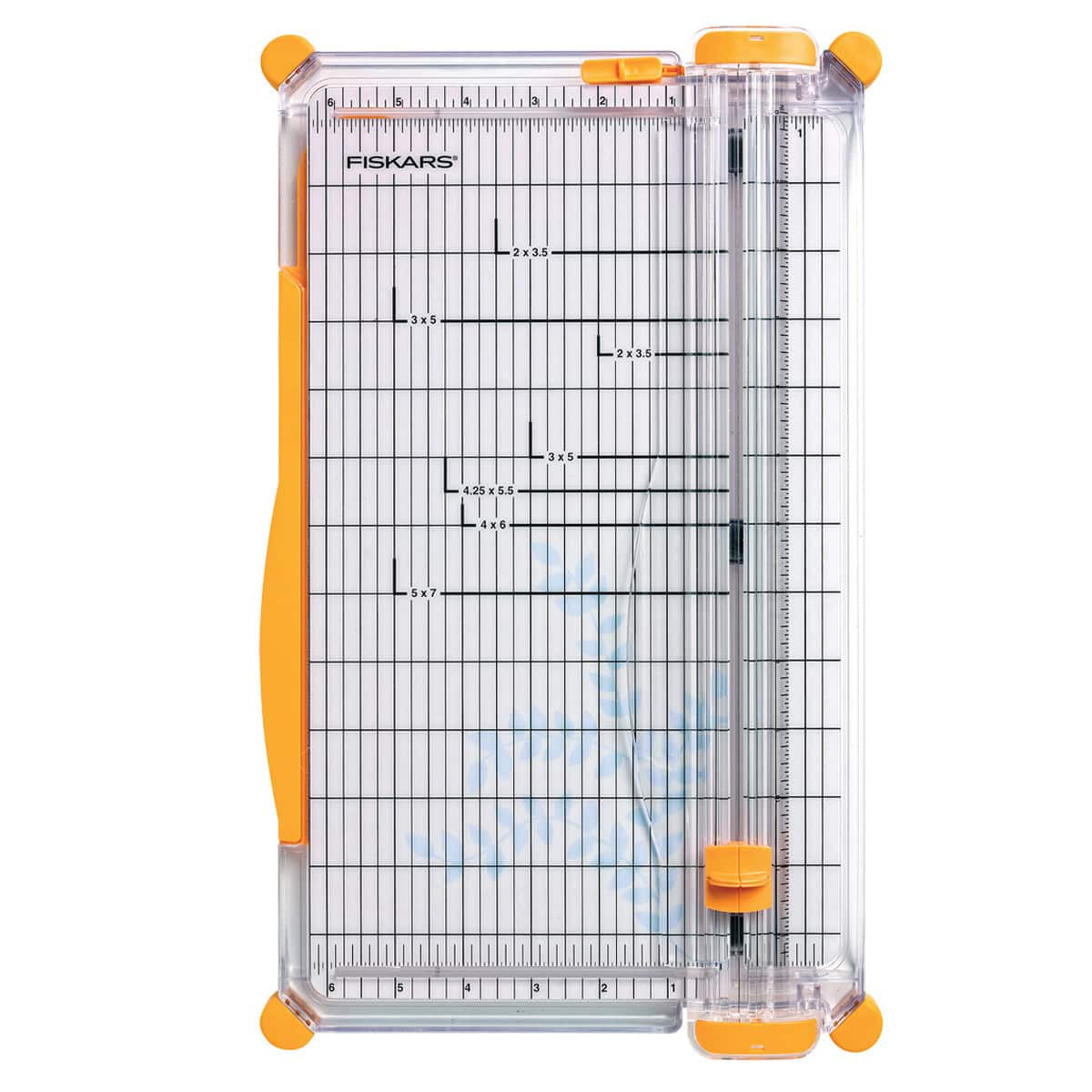

We’re getting close to a very streamlined production flow but cutting by hand was starting to slow us down due to the increasing number of cards we were developing. It was time for a trip to an office supply store.

Resources & tools

Now it was very tempting to pick up a paper trimmer to speed up cutting all the cards. You can cut through so many sheets of paper all at once. But we’re on a tight budget with limited apartment space, we weren’t going to find a permanent spot to house a full on guillotine.

We settled on this paper slicer. 10 sheets at a time is still a huge improvement over 1 and it only cost us 20$.

The paper cutter is the only money we’ve had to put into this project so far as our Magic the Gathering card collection has been a huge boon of resources.

We knew we’d need land cards because our game revolves around traversing over a “landscape��”. The basic land types from Magic were basically perfect right out the gate for this so we just sleeved some land cards, broke them into 4 decks, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter, and called it a day on land cards.

We did re-flavour and rename the base Magic lands. Partially because it would be obvious where the types originated but also because our land cards all have unique mechanics which felt like they could use more fitting names.

- Plains became Meadows

- Islands became Mists

- Forests became Mazes

- Mountain remain Mountains because it really fits our naming scheme

- Swamps became Mires

The development of the season decks did add a decent amount of complexity to running each play test because it slowed down both clean up and setup. Once programmed, a computer will manage the odds and deal out the landscape, but us humans need to manage it right now. So to speed up testing we did move out to shuffling all the season decks together into one deck because we can deal them out quickly thanks to the sleeve colour. A small compromise on sticking true to the future format but it feels like the right call for the moment to keep things moving.

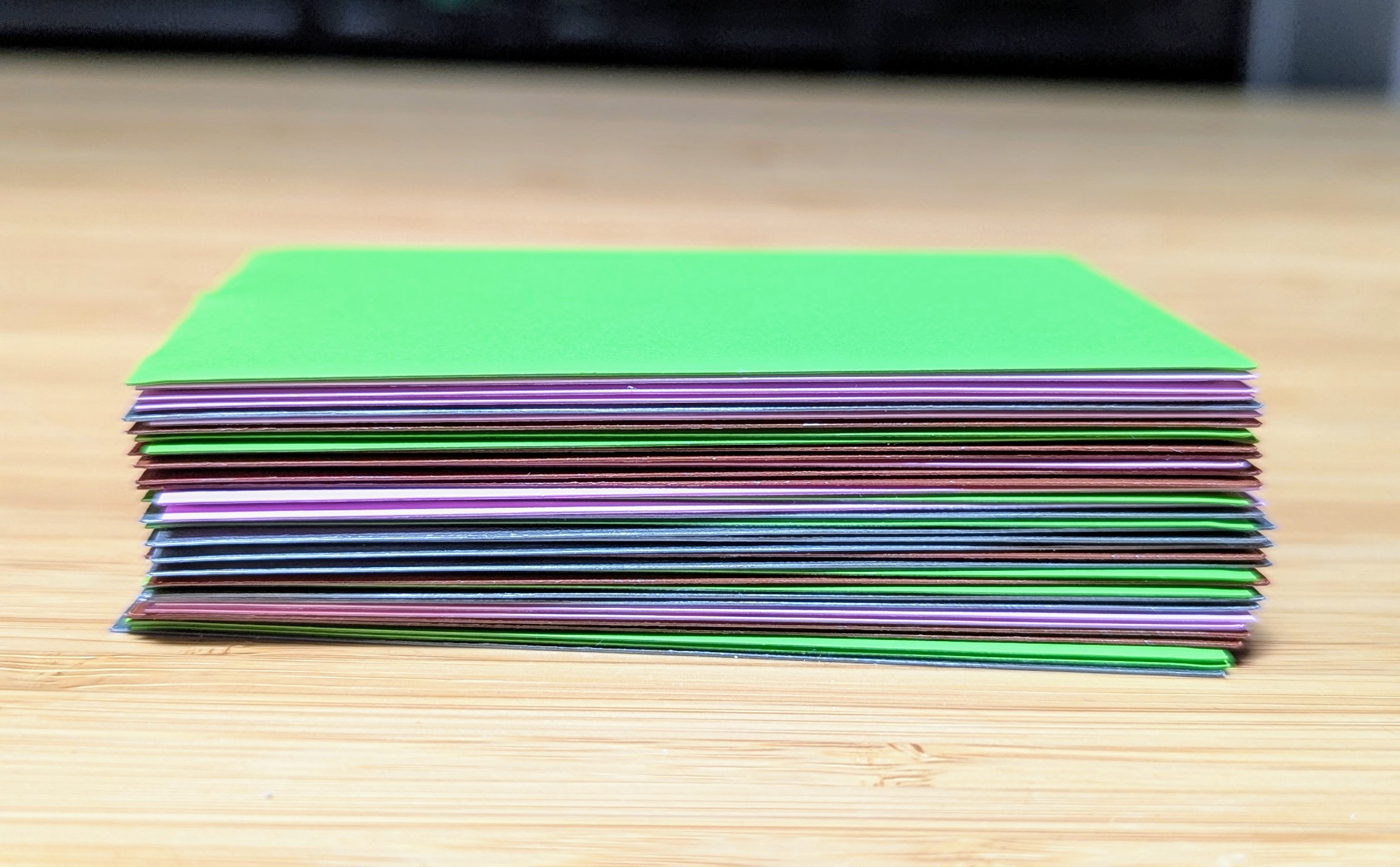

For our Fate Cards and Journey Cards (the cards the user plays) we sleeved a bunch of regular magic cards and then slid the printed versions of our cards over top so that when playing you still feel like you’re holding a nice solid playing card and not just printed loose paper.

As the complexity of our decks grew we broke down our different deck types by colours. 1 colour for our Fate cards, 1 colour for our Journey cards, and 1 colour for each season of land cards. This makes it easier to clean up after each play session and quickly short the cards back into their appropriate deck.

Some of our other Magic supplies have also come in handy so far too. When you buy certain release sets of magic cards you get to pop out little cardboard tabs that you put on top of your Magic cards during games to indicate things like status effects. We have a huge collection of these little things so we’ve been putting them to use to track our own game mechanics like the path our character has travelled and which pathways have Degraded. And thanks to some door tokens from the haunted house set from last year we have been able to use the doors to indicate Entrance and Exit of each level.

The whole project has basically been finding alternate uses from our existing game collection. Didn’t have to buy anything new, just re-purposed a lot of objects from our games shelf.

Play testing

Thanks to the incremental approach we took starting with the most basic rules we had: lay down a path (cards) on the landscape to traverse the landscape, we have been able to play test since day 1 of our paper prototype. We were playing every day for a while as we were building out the Fate Cards and the mechanics for each land type. Almost a week in and we managed to rope 2 friends into trying it out as well.

It was really validating to have new eyes on the game and seeing the rules start to click for people who aren’t us. Ideally we’d have someone new come by every week to get their feedback on the state of the game so far but it’s hard to lure friends into being testers.

It is the one main downside to paper prototyping, we can only share the game in person. We do have the rules fully typed out and it would be easy to share a PDF of the cards for other people to print out and play but it’s a huge request to make when you’re still constantly shifting cards around and actively developing. So we’ll probably just keep forcing anyone who comes into our home to play a round or two until we have a digital prototype.

Conclusion

Being able to see your game idea come together and become playable so quickly with paper prototyping has been amazing. It makes sense why so many teachers/textbooks/experienced game devs tout it as being so important. Just having physical things to touch and engage with has also made iteration faster both through

- Being able to test out new ideas on the fly

- Being able to think about physical limitations or expansions

It’s one thing to keep thinking about concepts and ideas in your head, but being able to move things around on a table really lets new neurons fire and make new connections in your brain much faster. This has been made extra clear from doing our game design homework where, during the exercises, they want you to spend time designing small games. We kept them all ideas/notes based and it took way more time than I thought it would to come up with ideas that felt good. Compared to our paper prototype where it feels like we come up with good, new ideas every time we play through it.

We’re likely to keep paper prototyping for a little while longer as we still have some ideas we want to put to the test that feel central to the main progression of the game. Once the main flow and mechanics make sense to us we’ll probably spend some time considering, and testing, balance.